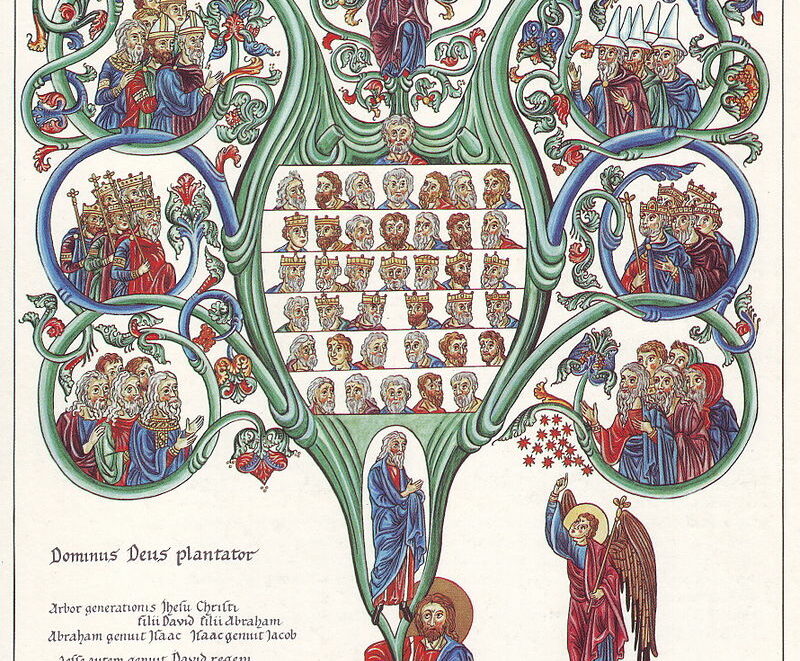

In our fourth meditation for Advent, Fr Euan reflects on the genealogy of Jesus according to St. Matthew, a difficult and strange reading for us, but one which is revealed as a story about our spiritual birth in baptism.

The genealogy of St Matthew (Mt 1:1-17) occurs twice in the readings at Mass over Christmas. Once in the third week of Advent, and a second time in the reading the Evening Mass, the Vigil Mass of Christmas Day, which this year will be celebrated at 5 pm on Christmas Eve. It is a challenge for preachers to say something about this genealogy, in fact it is a challenge even to read out loud the genealogy with its many difficult names, and our culture is not one which has much interest in long genealogies. British people seem rather disinterested in their ancestry, unless they are from the nobility. I once gave a talk on the infancy narratives where I said I was going to ask the small group a question. Before I asked the question, I wrote down on a piece of paper a prediction. The prediction was that only one person would be able to answer the question. I turned out to be right. The one person who could answer the question was a Canadian lady. The question was this: ‘Who can tell me where their great grandparents were born?’ The others in the group, this was in Newcastle, had no idea. The Canadian lady knew roughly were her great grandparents were born because they had emigrated to Canada from various parts of Europe, though mostly Britain.

I find that Australians, Canadians and people from the United States often know more about their ancestry than people in Britain, and I think it is because they are aware of being descended from immigrants. So they want to know where they came from. British people are often descended from immigrants too, but they can forget this quite easily. Why would the Jews be interested in their ancestors then? An obvious answer is that they wish to remain faithful to the covenant made with their ancestor Abraham. Jewish identity was bound up with the preservation of this memory that their father was a wandering Aramean, as the book of Deuteronomy puts it:

In the presence of Yahweh your God, you will then pronounce these words: “My father was a wandering Aramaean, who went down to Egypt with a small group of men, and stayed there, until he there became a great, powerful and numerous nation (Dt 26:5).

In fact the Israelites as they were known at first were immigrants to the Holy Land three times. They came in the personage of Abraham, came back from Egypt as the descendants of the sons of Jacob and a third time, after the time of Deuteronomy as those who returned from exile in Babylon. It was when they returned that they started to be called Jews, or Judaeans. The genealogy in St Matthew, even though it is rather stylised and does not purport to be an exhaustive genealogy, is typically Jewish in its concerns, and refers to the exile and return from Babylon. Holding on to their identity was very important then for these children of Abraham like no other people in the world, precisely because their hold on the Holy Land was so tenuous.

Many sermons on this Gospel focus on the four women who are mentioned, the four mothers in the long list of fathers. The fatherhood is important because fatherhood requires a cultural background, to maintain it. Motherhood is visible but to maintain a sense of fathers it is important to verbally acknowledge them, which is why surnames in many languages refer to the father. St Joseph is the last of the fathers mentioned, and it makes no difference to his fatherhood that he is not the biological father of Jesus. He acknowledges Jesus as his son, and that is what makes Jesus a Jew. The mention of the mothers in the genealogy is therefore striking. I have heard many sermons on these mothers and they usually stress the anomalous nature of these women becoming mothers. They are pagan, often producing their offspring in strange circumstances. It’s interesting but I would like to speak about something else in the genealogy, which is the names of the ancestors of St Joseph in the third part of the genealogy. The earlier names are people who are mentioned in the Old Testament. We know something about their story. We see too in these names a sort of earthly ascent. From the wandering Aramaean to the kings of Judah in the walled city of Jerusalem. It seems like progress of a sort. Yet the progress is really a sort of degeneration. The kings of Judah fail in their faith, as did the kings of the northern kingdom of Israel. This northern kingdom was destroyed by the Assyrians and that was that. This is not the end. In the genealogy we continue to hear about the men who would somehow maintain their Jewish identity in exile, and after the return to the Holy Land, where they would have to live under the Greeks and later the Romans.

Their names mean nothing to us. They are unknown, and they died in obscurity. Yet they must have remained faithful and from them would come St Joseph who would guard Jesus and be his earthly father. When they died, then they would no doubt learn to their great joy that their apparently worthless lives had not been for nothing but had been part of the great plan of God to bring salvation to the world.

The Genealogy though is based on a biological continuity, except when we come to St Joseph. There is a sort of spiritual paternity in St Joseph because he accepts Jesus as his son. For the Jews this was real fatherhood. The story of Tamar and Judah, although he is the biological father of Perez and Zerah, is actually about a more social fatherhood. I won’t go into the details since it is a complex story, based on considerations of family, which we would find strange. The important thing is that the genealogy ends with the fatherhood of St Joseph. The lack of biological continuity is actually a sign of what is to come. The Gospel of St Matthew is very preoccupied with the idea of God as Father. He is the Father of Jesus in a unique way, the fatherhood which makes his son co-equal with him, so that Jesus as Son of God is fully God. This does not contradict the idea of God as our father, as it is the Divine Sonship which brings us human beings into a relationship with God the Father which is more than just being created by him. The Divine Sonship is shared with us all.

This is why the list of the unknown names is so fascinating to me. The church itself in her two thousand years of history is full of unknown names whose fidelity has helped to pass on the sharing in the Divine Sonship of the Christ. Baptism, has replaced circumcision as the means of continuity in the Church. Baptism is spiritual and involves no permanent mark which can show that the person has received the sacrament. This is why the Church has to be organised, keeping records but also nurturing the faith and hope of the baptised. We are all involved in maintaining the reality of baptism, the gift of the Holy Spirit, who unites us to Christ. The Church therefore no longer has a biological continuity but a spiritual one. The spiritual continuity may seem fragile, indeed it is fragile, since we see how many baptised neglect the meaning of their baptism. Yet since it confers the power of the Spirit, those who do live their baptism, are able like the unknown fathers in Babylon and after the return from exile, to be responsible for the continuity of the Church. When we die, if we are saved, we will see how much our faith and hope came from the fidelity of those who preceded us.

Baptism therefore is a shared responsibility. This is why the end of the Gospel of St Matthew is so bound up with the genealogy. The people of God under the old dispensation were united by faith of a sort, certainly by fidelity to the covenant, but it was also a biological continuity. Now we have baptism, so the Gospel of St Matthew ends with these words.

Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you. And remember, I am with you always, to the end of the age (Mt 28:19-20).

In these words, Christ teaches us that there is a genealogy from him as well as a genealogy to him, which continues throughout history, no longer a chain of fathers, but a great tapestry of many people spreading through the world. Through our shared baptism, we are able to give birth to each other, the spiritual birth which echoes in time the divine birth of eternity.